This Is A Twisted Web And We Are Not Finished Untangling It, Not Yet

Benoit Blanc

Keeping up with at least 800 words worth of blog posts a month is an almost daunting task when you feel there isn’t much to write about that interests you. Thoughts on pop culture, both musically and otherwise, are usually things I keep to myself. There are, however, certain types of stories that I feel I could write about for thousands of words with ease, which is helpful if these stories are the topics of any essays I should need to write. In this case, however, I wanted to focus on the rise of the “cosy” murder mystery genre. The term cosy here is used lightly, given it is a subjective term, and it seems like even the most gruesome true crime stories can be “cosy” to people if presented in the right way.

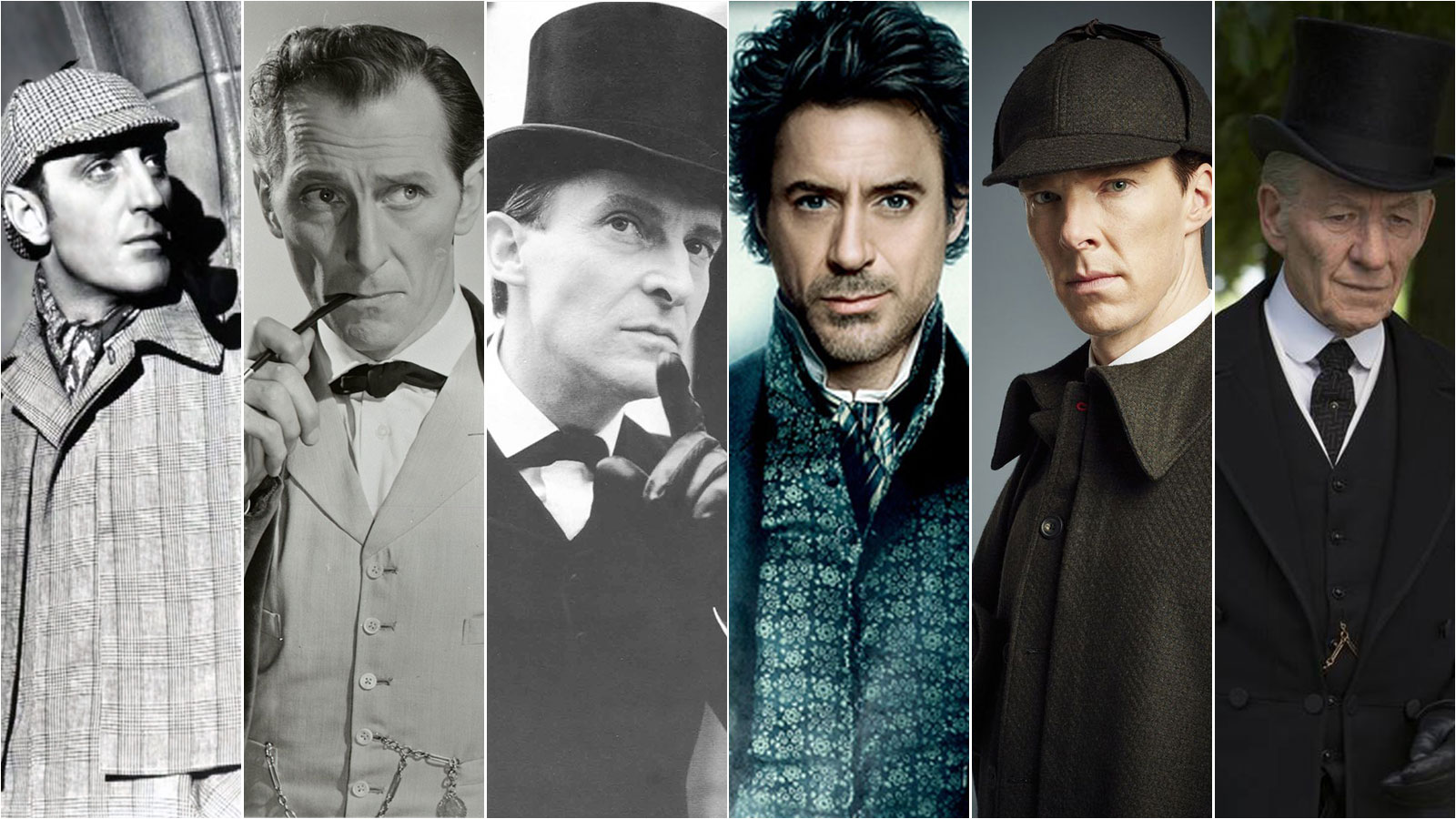

Murder mystery as a genre always seems to be around, especially in book form, but it seems to have taken a recent series of hits to see mysteries presented on the silver screen rather than the television screen. Adaptations of Agatha Christie or Arthur Conan Doyle stories never seem to be out of production, but since the rise of televisions and the format of episodic content, detective stories tend to be available primarily in our home rather than the cinema. Besides constant adaptations, there has also been a steady increase in original TV shows with no literary origin, and non-English shows, like the many gritty Scandinavian dramas, have proven especially popular to viewers around the world. However, it seems as though there is a resurgence in mystery films in recent years, with some more successful than others, thanks in part to the Kenneth Branagh adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express. Having watched both of Branagh’s Christie adaptations, and enjoying them, I do not wish to focus on either. Because two other films have been released this year that I feel are better examples of modern murder mysteries.

See How They Run, a recent example of the murder-mystery resurgence, starts off with an interesting premise. Set in 1953 London, the film cleverly references and utilises not only classic tropes and techniques found in the likes of Sherlock Holmes or Poirot, but also uses Christie’s The Mousetrap as the main backdrop of the murder. It is very much a whodunit within a whodunit. While actors portray actors portraying characters, like Harris Dickinson’s portrayal of Richard Attenborough’s portrayal of Sergeant Trotter, more subtle references are found in the film’s original characters, like Inspector Stoppard, who is presumably named after playwriter Tom Stoppard, and even the hotel manager correcting Constable Stalker that he is not French but Belgian seems to be an allusion to Hercule Poirot. Many such moments occur, with the film almost spelling out not the mystery but the way the film will be presented with characters bemoaning the use of flashbacks in films right before one occurs, to the play in the film asking the mystery to remain unspoilt for others. And while I enjoyed and recommend the film and its many layers, I feel that another detective has recently emerged in one of the most sharply written series of films over the past few years.

Detective Benoit Blanc comes from the mind of writer/director Rian Johnson, who proudly wears his influences on his sleeves. In 2019’s Knives Out, Johnson crafted an up-to-date murder mystery that hooked viewers with its twists and revelations to such a degree that Netflix reportedly paid $400M for the rights to two sequels, a price which doesn’t include the tens of millions required for each production. While the first one dealt with a similar story to that found in many a detective story, from Sherlock Holmes to Poirot (in this case, a family fighting over an inheritance worth millions), the second one can point to 1973’s The Last of Sheila as its primary influence.

The first fruit of Netflix’s $400M investment is Glass Onion, which moves away from the homely Massachusetts setting of the first film and focuses on the ‘new-money’ of Silicon Valley rather than the ‘old-money’ of the Thrombey’s in the first one. And while the first film’s primary twist occurs early on, this second outing of Blanc feels like a more traditional whodunit, where the murder doesn’t even occur at the outset. Benoit Blanc as a character is also a much bigger focus than he was in the first film, where he could even appear as an antagonist to Marta, the film’s primary character. But like any good writer of detective-based mystery, Johnson does not focus solely on the character but rather the mystery being presented. This falls in line with how Conan Doyle would characterise Holmes, via Watson, through the mystery rather than have the mystery occur around Holmes, a mistake at least one Television adaptation made, and which I feel would lessen the impact of the mystery in the narrative. The detectives found in the stories can be presented as part of the mystery, perhaps being involved with a suspect or the victim, but shouldn’t be the reason why there is a mystery to begin with. This isn’t to say there should be no character development between chapters, books, episodes, or films, but the detective in the stories should usually remain the one constant, especially when there is often a brand-new cast of characters in each story. Blanc is introduced in the first film in much the same way Holmes would be, as an outsider to the story trying to solve the puzzle and look for clues, while in the sequel we are introduced to Blanc before the mystery begins, bored out of his mind thanks to the pandemic forcing him to stay at home. And while I could go on, I feel I have written enough on the subject for the moment, lest I run out of material for future posts, and if this blog should be the basis for any future ideas, I hope I can look back on posts like these to try and find ideas to use.